Stop tracking vanity metrics

In this post I'll be sharing common analytics pitfalls and a simple system for tracking better metrics

Even though product analytics is considered a key skill for every Product Manager, I strongly believe we have a long way to go to really raise our analytical skills across the community. I’ve shared my thoughts on this in my previous article The Big Gap of Product and Analytics, and received a lot of feedback that (unfortunately) confirmed my observations - the learning curve for Product Managers to get confident in product analytics is extremely steep. I thought it’s worth diving deeper into this topic and dedicate a whole series of articles to this.

I’ve personally fallen into various analytics traps and focused on the wrong data many many times. In the upcoming posts I want to share some of my biggest learnings and the most common patterns and pitfalls I’ve observed when coaching and interviewing Product Managers.

Why do we love vanity metrics so much?

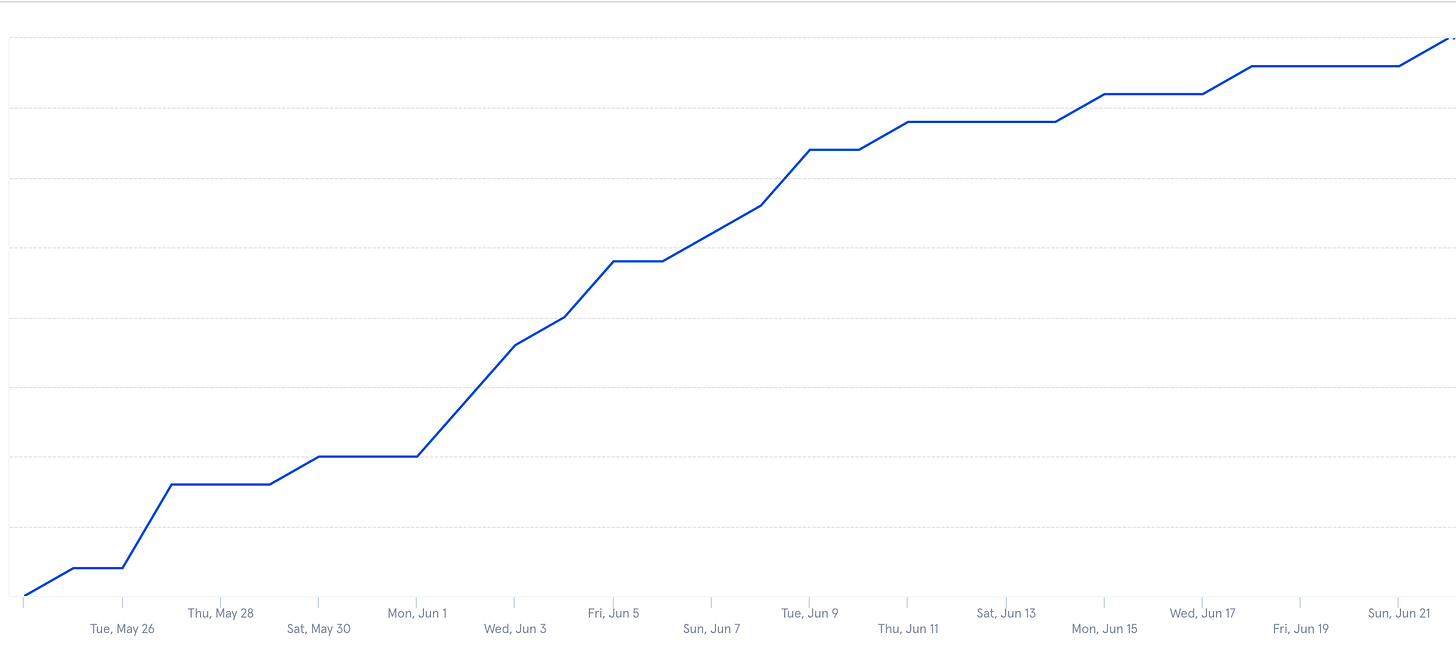

I am currently running a business visitor management SaaS product which is in its early growth stage. I shared some graphs previously that showed the acquisition of our product i.e. sign ups over the last 30 days when we first launched.

The numbers seemed to be going up, so we were pretty happy about the momentum.

But to everyone’s surprise, it didn’t really result in an increase in conversions to paid plans, and nothing changed in our monthly recurring revenue from the sign ups that month.

Looking at that graph again, I asked myself the following questions:

What insight is this giving us about our product?

What actions will we take based on this insight?

Has this month been a good month? 🤷🏼♀️

You can probably tell by now that this is actually a terrible chart to look at.

Yes, the user base is growing. We started to run online ads, so this was kind of expected.

The first problem is it doesn’t give us any insight about the product. At best it may show if something is seriously wrong with our landing page and people don’t even find the sign up button. I’d very much hope we got that one right.

Secondly, this graph doesn’t give us any context of how well we’ve been performing over the last 30 days in terms of our acquisition. There is no comparison to our marketing spend or other time periods - just a simple total number that doesn’t really tell us anything useful on its own.

Lastly, the outcomes of this graph don’t really change our behaviour in any way. Again, maybe only if suddenly people don’t find the sign up button anymore.

The number of sign ups over time in my graph is a great example of a classic vanity metric. It doesn’t give us any actionable insight.

You might have also noticed it’s a cumulative chart. This means that it adds signs ups and shows the total number, which means the chart can only go up or worst case plateau as time progresses.

So why do we keep looking at those charts?

Because vanity metrics make us feel good. Since the number never goes down, vanity metrics are good for our ego. Bonus: they usually go down well at stakeholder presentations..

Popular examples of vanity metrics

Number of sign ups is not the only vanity metrics I see Product Managers and insights teams focus on. Other examples of vanity metrics I often come across are:

Number of page views

Number of unique visitors

Number of followers / likes

Time spent on site (session length)

Number of downloads

A lot of these metrics like page views and session length still stem from the good old website analytics days when it was all about filling the funnel, but not really caring about what they do next. This may still be helpful if your business model is purely based on views or clicks (e.g. advertising revenue), and session length might be quite valuable if you’re looking after an entertainment product like Netflix, but those are the only use cases I can currently think of. For most products, those metrics are not very useful.

Yes you should factor in your overall reach, but what we really need to get better at is analysing our product usage - do our new users actually activate the product, do they engage with it and do they keep coming back?

Other ways we lie to ourselves

I also often hear in interviews that analytics knowledge and data insights get hidden away in dark mysterious corners of offices, with event names that no one but a couple of highly specialised analysts understand. Every month those specialists would meet with various product teams in an attempt to share and translate some of their findings.

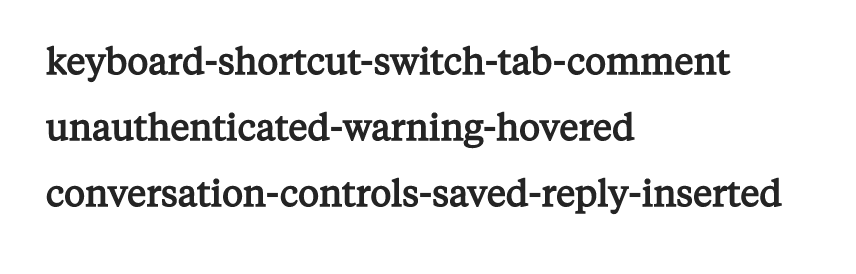

The support and business messenger tool Intercom shared their learnings from doing a massive events clean up a few years ago. Basically they had around 350 events for their product that kind of looked like this:

I think they make a great point. The key to effective product analytics is to make the events and insights easy to understand for absolutely everyone, and to share those data insights regularly with the whole product team.

And yes, this means discovering and sharing some ugly truths about our real engagement end retention numbers. But if we really want to build better products, we need to take ownership of those numbers. Any good product team should be more motivated than ever to solve those problems once they know those hard truths.

How we can do better

First of all we need to focus more on good metrics that give us real insights about our products. We should focus our attention more on whether our customers activate the product, whether they get the full value after signing up, how often and how deeply they engage with our product features, and whether they remain long term retained customers or churn after a while.

Another key part I touched on earlier is that the insights we get from our analytics need to actually drive actions. What I have observed is that most teams make data informed decisions, but the best product teams have a data driven culture.

To really understand if a metric is good or bad, we need to put numbers into context. At the very minimum you want to try to compare a number over different time periods.

The most effective way to get more useful insights however is to use ratios instead of total numbers. As an example, accountants do not only look at the total revenue made over time, but also how their operating expenses and product costs have evolved, and how this affects their margin (a good example of a useful ratio). Ratios are inherently comparative.

In my case for tracking sign ups to my visitor management system, it would be a lot more helpful if I could compare the last 30 days vs the previous 30 days, put it in relation with our marketing spend, or compare the number of sign ups with the number of conversions to paid plans. Or even better - compare the conversions over number of sign ups this month vs previous months. If this ratio is declining, it might mean we’re attracting lower quality leads, or maybe a recent change to our activation experience means people are more likely to churn after signing up.

And lastly, democratise your data and make sure your events and reports are easy to understand, so your product team can discuss and share them between each other.

I created a simple system to keep you in check whether you’re tracking good metrics:

..and now repeat after me! 🎤🎶

Keep this checklist in mind whenever you look at your analytics reports and insights. Check each metric against those points and be honest with yourself. It takes discipline to not fall back into reporting on vanity metrics, but it will make you and your team become truly data driven.

Want to read more on this topic?

I am proud to share I have launched my first ebook on how to get more insights from your data! The Insights Driven Product Manager is your essential guide on how to track less and get more insights from your data to make better product decisions. It includes practical frameworks and worksheets that you can apply to your products straight away.